#29 Phenomenological clusters and visionary states of expectation and surprise

The latest batch of neurophenomenology-related papers I read were Lutz (2002); Lutz, Lachaux, Martinerie, and Varela (2002); and Thompson and Lutz (2003). I only skimmed the last paper because it turned out to be an earlier draft of the more fleshed out chapter they published in 2005 with Cosmelli, and which I already read (see how their paper—“Neurophenomenology: An Introduction for Neurophilosophers”—inspired that day’s stream).

With the above exception out of the way, the theme for this stream centers around the work of Antoine Lutz and his colleagues. Lutz worked with Varela, in fact their Lutz et al (2002) paper appears to be the first documented case study of neurophenomenological research. I speak about this study somewhat in blog post/stream #26 (see above link). However, it was great to read the original study and the follow-up paper by Lutz (2002) for a more in-depth analysis of the findings.

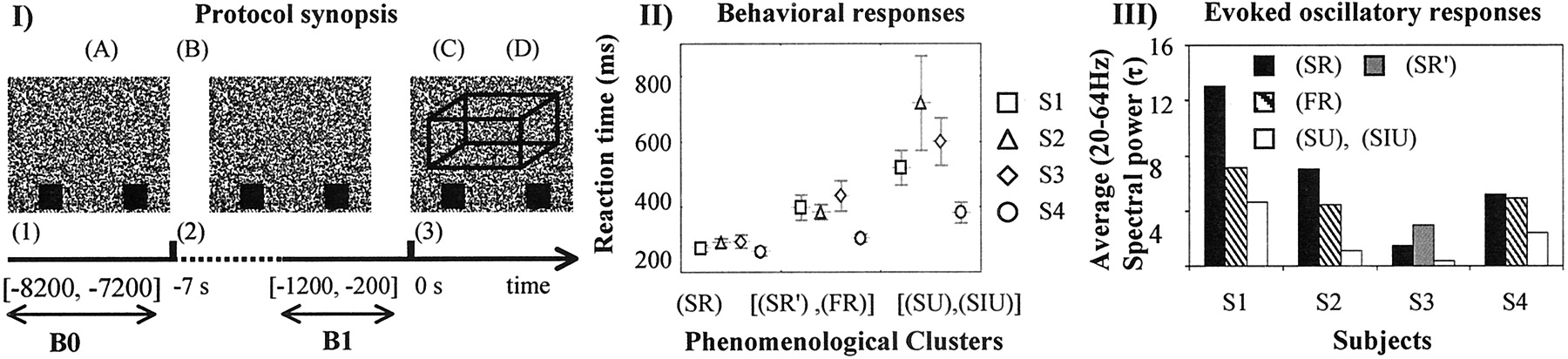

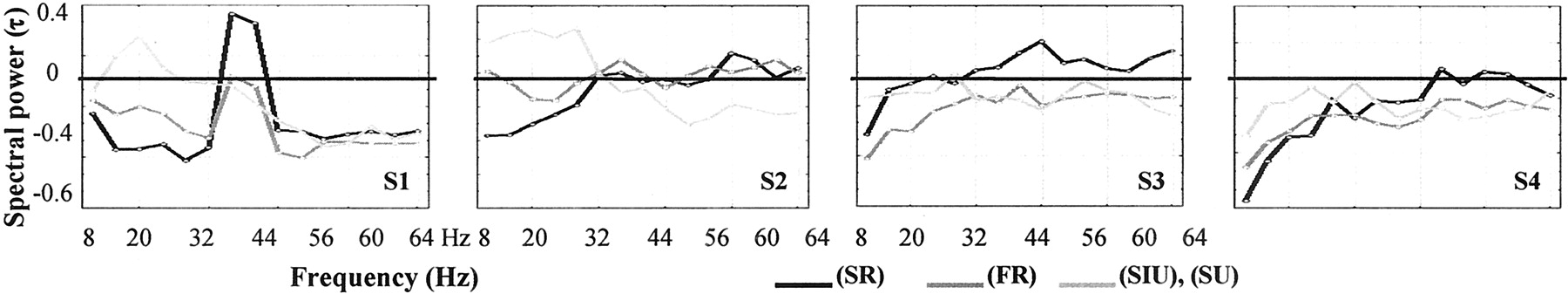

What really strikes me about Lutz et al’s (2002) findings is that “dynamical neural signatures” (DNS), as they call them, match and even predict subjects’ mental states. For example, three states of phenomenological clusters were identified as: steady readiness, fragmented readiness, and unreadiness. Steady readiness involves a state of expectation and alertness, and just before the subject noticed a 3D image pop out of the autostereogram (an optical illusion that involves crossing one’s eyes to see the hidden object), the EEG showed signals of stimuli detection before the subject indicated its detection. On the other hand, when subjects were distracted and in a state of unreadiness, they were surprised or caught off-guard by the appearance of the 3D image, and the EEG did not register any anticipatory signals. The neural signals were different in both cases. The conscious act of expectation, of waiting for something to appear, actually registered the stimuli in the EEG, moments before the subject pushed the button indicating they saw it. How is this possible; what does it mean?

Their study suggests that we perceive things before we even know we perceive them when in an attentive and expecting state. This might allow the human being to slow down time, to know how to move or act in any given situation. I’m reminded of athletes who speak of slowed down time, boxers who just know where their opponents’ next punch will go, etc. There seems to be a predictive nature to the brain, not in a filling-in-the-blanks kind of way, but of knowing whether a thing or a specific thing is approaching. If I could ask a question to the above researchers, I’d want to know whether there is any connection with the Lutz et al (2002) study and the theory of predictive coding/processing written by for example Anil Seth, Alva Noë, and others. Further, and related to my interests, these empirical studies make strong claims relating to the brain and perception, and so I wonder how psychedelic users experience/see what they do.

A few things come to mind. It seems to me that users will fall into one of four different experiential scenarios: (1) users expect to see something they’ve (a) seen before or (b) never before, or (2) users are surprised to see something they’ve (a) seen before or (b) never before. The phenomenological cluster of steady readiness would be 1a; fragmented readiness as 1b and 2a; and unreadiness as 2b. If you’re expecting to see something that you’ve seen before, either the exact same object or an object given/presented in the same manner, your brain will register it moments before you realize you do according to Lutz et al’s (2002) concept of dynamical neural signatures saying this to be so. If you’ve seen X or the way in which X is given to consciousness, during a previous psychedelic experience (steady readiness), then you’re prepared the next time you take that psychedelic because you have a mental repository of things experienced and their givenness. You have an idea of what you’re getting yourself into and how the substance affects your being and most importantly how it affects consciousness. Knowing what you know about the experience from previous excursions, you can still be surprised (fragmented readiness) by novel things you had never seen up until then or you’re surprised by reoccurring phenomena in your subsequent experiences. Finally, being surprised by something you’ve never seen before falls into the category of unreadiness. You don’t know what you don’t know, and thus when you first acquaint yourself with this unknown unknown, it can be surprising, amazingly positive, or frightful as fuck.

Back to dynamical neural signatures: I’m still fascinated by the brain registering the stimuli before the subject indicates awareness of it. Since researchers made use of an autostereogram, it is a fact that the image is there. Their eyes presumably can see it, or the subject intuitively knows that it’s there. All that is required is a shift in visual perception for the eyes to see it. So, and this is where it gets freaky and highly speculative: are there things around us in a nonphysical sense that our brain registers but our eyes do not unless we change our perception by means of some catalytic agent, such as a psychedelic? I’m going to end this thought here because I have numerous notes on this idea that I’m not ready to share at present…

Lutz, A. (2002). Toward a neurophenomenology as an account of generative passages: A first empirical case study. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 1(2), 133-167.

Lutz, A., Lachaux, J. P., Martinerie, J., & Varela, F. J. (2002). Guiding the study of brain dynamics by using first-person data: Synchrony patterns correlate with ongoing conscious states during a simple visual task. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(3), 1586-1591.

Lutz, A., & Thompson, E. (2003). Neurophenomenology: Integrating Subjective Experience and Brain Dynamics in the Neuroscience of Consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 10(9-10), 31-52.